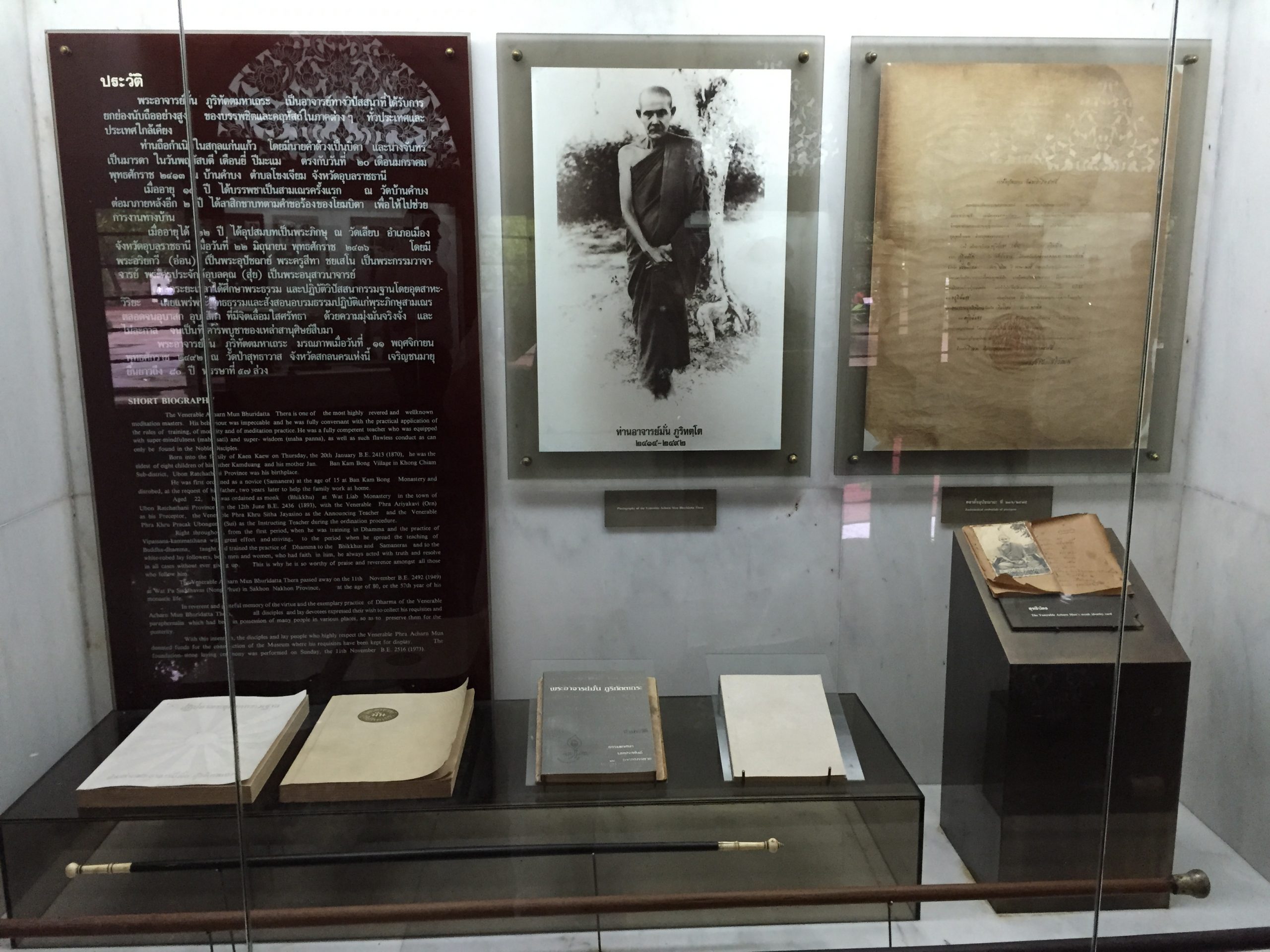

Phra Ajaan Mun Bhūridatta Mahā Thera

(1870-1949)

The following short biographical account of the life of Luang Puu (LP) Mun was written by Phra Ajaan Ṭhānissaro as the introduction to his translation of a collection of the teachings of LP Mun, entitled, Muttodaya — A Heart Released. A full biography of LP Mun was written by Phra Ajaan Maha Boowa and translated into English by Phra Ajaan Dick Sīlaratano. This book is a truly inspiring account of the life of this grand master and founder of the Forest Meditation Tradition. The reader is strongly recommended to read it to gain a full understanding of the life style and practice of this important person in order to appreciate what the tradition is all about.

LP Mun Bhūridatta Thera was born in 1870 in Baan Kham Bong, a farming village in Ubon Ratchathani province, northeastern Thailand. Ordained as a Buddhist monk in 1893, he spent the remainder of his life wandering through Thailand, Burma, and Laos, dwelling for the most part in the forest, engaged in the practice of meditation. He attracted an enormous following of students and, together with his teacher, LP Sao Kantasīlo, was responsible for the establishing of the forest ascetic tradition that has now spread throughout Thailand and to several countries abroad. He passed away in 1949 at Wat Paa Suddhāvāsa, Sakon Nakhorn province.

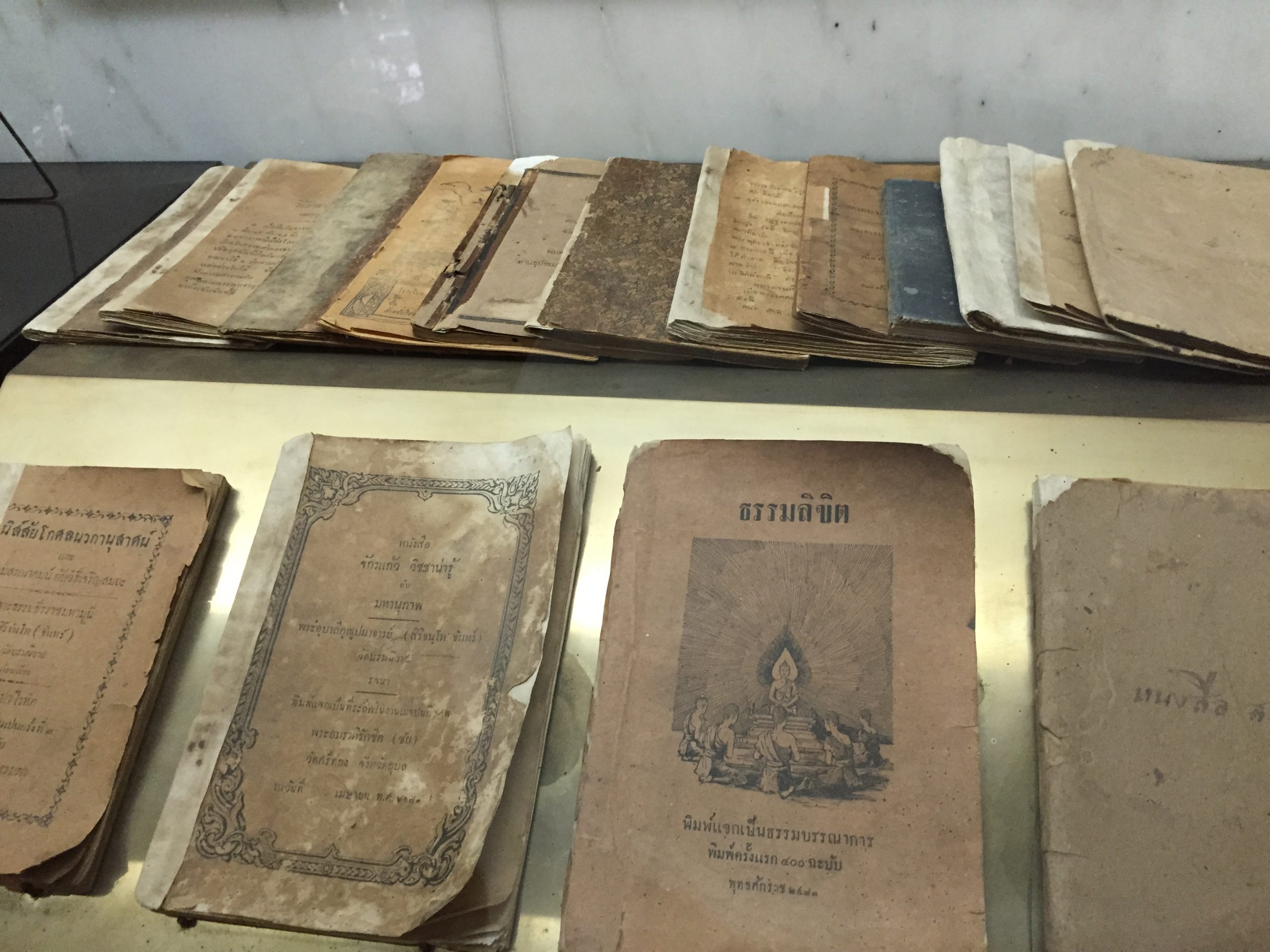

Much has been written about his life, but very little was recorded of his teachings during his lifetime. Most of his teachings he left in the form of people: the students whose lives were profoundly shaped by the experience of living and practicing meditation under his guidance. One of the pieces that was recorded is translated here. A Heart Released (Muttodaya) is a record of passages from his sermons, made during the years 1944–45 by two monks who were staying under his guidance, and edited by a third monk, an ecclesiastical official who frequently visited him for instruction in meditation. The first edition of the book was printed with his permission for free distribution to the public. The title of the book was taken from a comment made by the Ven. Chao Khun Upāli Guṇīpamācariya (Jan Siricando) who, after listening to a sermon delivered by LP Mun on the root themes of meditation, praised the sermon as having been delivered with ‘muttodaya’ — a heart released — and as conveying the heart of release.

The unusual style of LP Mun’s sermons may be explained in part by the fact that in the days before his ordination he was skilled in a popular form of informal village entertainment called maw lam. Maw lam is a contest in extemporaneous rhyming, usually reproducing the war between the sexes, in which the battle of wits can become quite fierce. Much use is made of word play: riddles, puns, innuendoes, metaphors, and simple playing with the sounds of words. The sense of language that LP Mun developed in maw lam he carried over into his teachings after becoming a monk. Often he would teach his students in extemporaneous puns and rhymes. This sort of word play he even applied to the Pali language.

This sort of rhetorical style has gone out of fashion in the West and is going out of style today even in Thailand, but in the Thailand of LP Mun’s time it was held in high regard as a sign of quick intelligence and a subtle mind.

LP Mun was able to use it with finesse as an effective teaching method, forcing his students to become more quick-witted and alert to implications, correspondences, multiple levels of meaning, and the elusiveness of language; to be less dogmatic in their attachments to the meanings of words, and less inclined to look for the truth in terms of language. As LP Mun once told a pair of visiting monks who were proud of their command of the medieval text, The Path of Purification, the niddesa (analytical expositions) on virtue, concentration, and discernment contained in that work were simply nidāna (fables or stories). If they wanted to know the truth of virtue, concentration, and discernment, they would have to bring these qualities into being in their own hearts and minds.

One can gain a glimpse of LP Mun’s teaching style from the autobiographies of some of his students. A good example is that of Than Phor Lee Dhammadharo, who wrote in his own autobiography:

“Staying with Phra Ajaan Mun was very good for me, but also very hard. I had to be willing to learn everything anew… Some days he’d be cross with me, saying that I was messy, that I never put anything in the right place — but he’d never tell me what the right places were… To be able to stay with him any length of time, you had to be very observant and very circumspect. You couldn’t leave footprints on the fl oor, you couldn’t make noise when you swallowed water or opened the windows or doors. There had to be a science to everything you did — hanging out robes… arranging bedding, everything. Otherwise, he’d drive you out, even in the middle of the Rains Retreat. Even then, you’d just have to take it, and try to use your powers of observation.

“In other matters, such as sitting and walking meditation, he trained me in every way, to my complete satisfaction. But I was able to keep up with him at best only about 60 percent of the time.”

The following passages are drawn from the autobiography of LP Mun:

LP Mun was born into a traditional Buddhist family on Thursday, 20 January 1870. His birthplace was the village of Ban Khambong in the Klongjiam district of Ubon Ratchathani province.

His father’s name was Khamduang; his mother’s, Jun; and his family surname, Kaenkaew. He was the eldest of eight siblings. A child of small stature with fair complexion, he was naturally quick, energetic, intelligent, and resourceful.

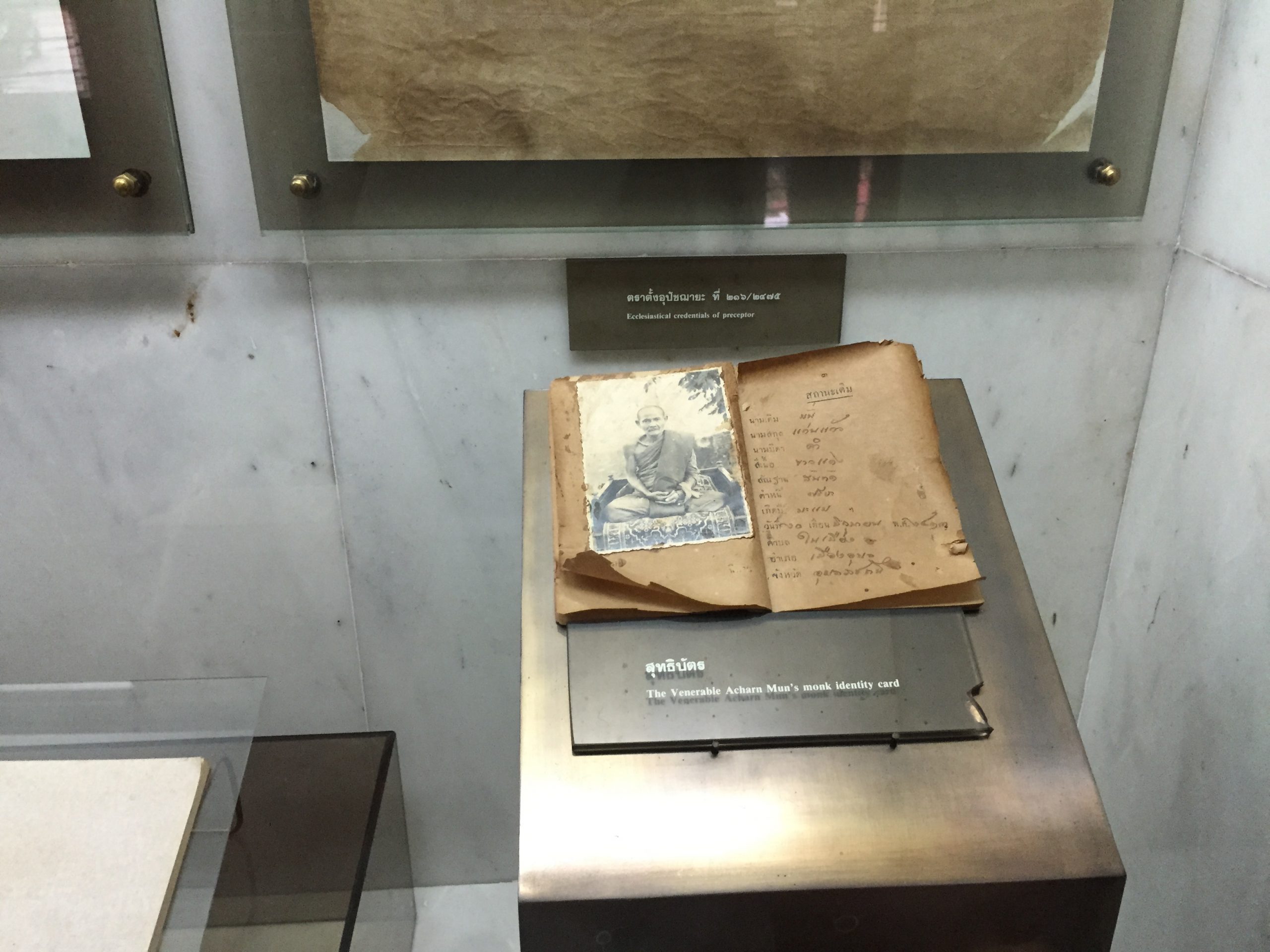

At the age of 15 he ordained as a novice in his village monastery, where he developed an enthusiasm for the study of Dhamma, memorizing the texts with exceptional speed. Two years after his ordination, his father requested him to give up the monkhood in order to help out at home. However, due to his strong affnity for the monkhood, he again requested ordination when he attained the age of 22. His parents willingly gave him their permission, and he was ordained a Bhikkhu on June 12, 1893, at Wat Liap, in the provincial town of Ubon Ratchathani. His preceptor was the Venerable Ariyakawi, his Announcing Teacher was Phra Khru Prajuk Ubonkhun, and his Ordination Teacher (kammavācācariya) was Phra Khru Sitha. He was given the monastic name, “Bhūridatta” and he resided in Wat Liap, in LP Sao’s meditation center.

He applied himself diligently to the practice of meditation under the guidance of LP Sao. Soon after, he had a prophetic dream indicating that he would attain what he sought if he persevered in his efforts at the practice. In the words of LP Maha Boowa:

“From then on, with renewed determination, LP Mun meditated intensively, unrelenting in his efforts to constantly repeat “Buddho” as he conducted all his daily affairs. At the same time, he very carefully observed the austere dhutaṅga practices that he undertook at the time of his ordination and continued to practice for the rest of his life. The dhutaṅgas he voluntarily undertook were: wearing only robes made from discarded cloth — not accepting robes directly offered by lay supporters; going on almsround every day without fail — except days when he decided to fast; accepting and eating only food received in his alms bowl — never receiving food offered after his almsround; eating only one meal a day — never eating after the one meal; eating only out of the alms bowl — never eating food that is not inside the one vessel; living in the forest — which means wandering through forested terrain, living and sleeping in the wilds, in the mountains or valleys; some time spent living under a canopy of trees, in a cave, or under an overhanging cliff ; and wearing only his three principal robes — the outer robe, the upper robe, and the lower robe, with the addition of a bathing cloth which is necessary to have nowadays.”

He spent the last five years of his life at Baan Nong Pheu Monastery, Sakhon Nakorn province. Because of his advanced age — he was 75 years old when he began staying there — he remained within the confines of the monastery all year, unable to wander extensively as he had in the past. During these last few years, he concentrated his efforts on assisting the monks and laity more than at other places that he had stayed in before.

Towards the end of his life, when his physical condition was showing signs of rapid deterioration, LP Mun asked that his disciples move him from the small monastery of Baan Nong Pheu to Wat Paa Suddhāvāsa in the present city of Sakon Nakhorn, as he did not want large numbers of animals to be slaughtered to feed the many monastic and lay attendees who would come to his funeral. In comparison, Sakhon Nakhorn was a city and so had a large market for the attendees to depend on. Hence, his disciples took him by stages from the forests of Baan Nong Pheu, at first by foot, to Ban Phu. From Ban Phu, they were transported in trucks to Wat Paa Suddhāvāsa in Sakon Nakhorn. LP Mun and his disciples arrived there at noon, 10 November 1949, and he was conveyed to a hut in the monastery to rest, as he had been sedated for the journey. His disciples gathered around him to watch over him. Around mid-night, he began to wake up, but the signs of the body’s deterioration were clear to his disciples.

In the words of LP Maha Boowa: “As the minutes passed, his breathing gradually became softer and more refined. No one took his eyes off him for it was obvious the end was fast approaching. His breathing continued to grow weaker and weaker until it was barely discernible. A few seconds later, it appeared to cease, but it ended so delicately that no one present could determine just when he passed away. His physical appearance revealed nothing abnormal — so different from the death of the ordinary person. Despite the fact that all his disciples observed his final moments with unblinking attention, not one of them was able to say with any conviction: ‘That was precisely the moment when Ajaan Mun finally took leave of this dismal world’”

Chao Khun Dhammacedi of Wat Bodhisomphon in Udorn Thani, a senior disciple of LP Mun finally announced that LP Mun had passed away, after seeing no apparent signs of life. Checking his watch, he noted that the time was 2:23 a.m., 11 November, 1949.

Here are some excerpts from his teachings recorded in Muttodaya:

“They dwell without fermentation, having entered the release through concentration and release through discernment realized and verified by themselves in the very present.”

This passage from the Canon shows that arahants of no matter what sort reach both release through concentration and release through discernment, free from fermentations in the present. No distinctions are made, saying that this or that group reaches release only through concentration or only through discernment. The explanation given by the Commentators — that release through concentration pertains to those arahants who develop concentration first, while release through discernment pertains to the ‘dry insight’ arahants, who develop insight exclusively without having first developed concentration — runs counter to the path. The eightfold path includes both right view and right concentration. A person who is to gain release has to develop all eight factors of the path. Otherwise he or she won’t be able to gain release. The threefold training includes both concentration and discernment. A person who is to attain knowledge of the ending of mental fermentations has to develop all three parts of the threefold training completely.

This is why we say that arahants of every sort have to reach both release through concentration and release through discernment.

The four noble truths — suffering, its cause, its cessation, and the path to its cessation — are activities in that each truth has an aspect that has to be done: Suffering has to be comprehended, its cause abandoned, its cessation made clear, and the path to its cessation developed. All of these are aspects that have to be done — and if they have to be done, they must be activities. So we can conclude that all four truths are activities. This is in keeping with the first verse quoted above, which speaks of the four truths as feet, stair treads, or steps that must be taken for the task to be finished.

What follows is thus termed activityless-ness — like writing the numerals 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0, then erasing 1 through 9, leaving just 0, and not writing anything more. What is left is read as “zero,” but it doesn’t have any value at all. You can’t use it to add, subtract, multiply, or divide with any other numerals, yet at the same time you can’t say that it doesn’t exist, for there it is: 0 (zero).

This is like the discernment that knows all around, because it destroys the activity of supposing. In other words, it erases supposing completely and doesn’t become involved with or hold on to any supposings at all.

With the words ‘erasing’ or ‘destroying’ the activity of supposing, the question arises, ‘When supposing is entirely destroyed, where will we stay?’ The answer is that we will stay in a place that isn’t supposed: right there with activityless-ness.

The Lord Buddha taught that his Dhamma, when placed in the heart of an ordinary run-of-the-mill person, is bound to be thoroughly corrupted (saddhamma-paṭirūpa); but if placed in the heart of a Noble One, it is bound to be genuinely pure and authentic, something that at the same time can neither be effaced nor obscured.

So as long as we are devoting ourselves merely to the theoretical study of the Dhamma, it can’t serve us well. Only when we have trained our hearts to eliminate their ‘chameleons’ — their corruptions (upakkilesa) — will it benefit us in full measure. And only then will the true Dhamma be kept pure, free from distortions and deviations from its original principles.

A very rare photo of LP Man with his disciples, from the left to right: LP Khao, LP Louis, LP Maha Boowa.

In memory of LP Man displaying relics and personal effects notice that the shoulder bone has turned crystalline.