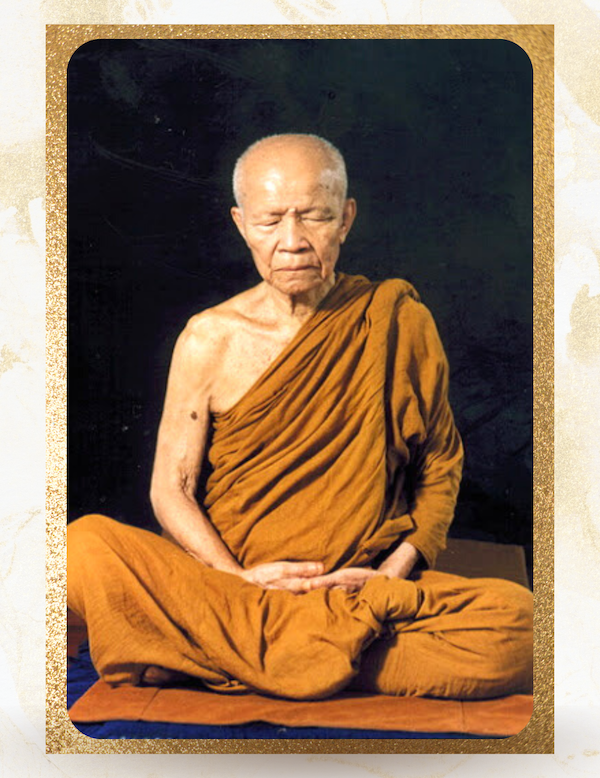

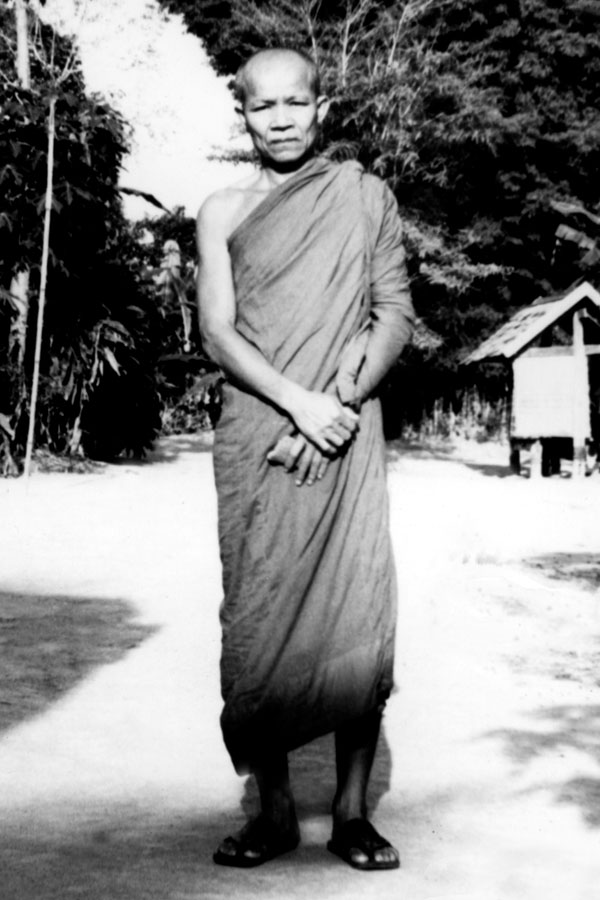

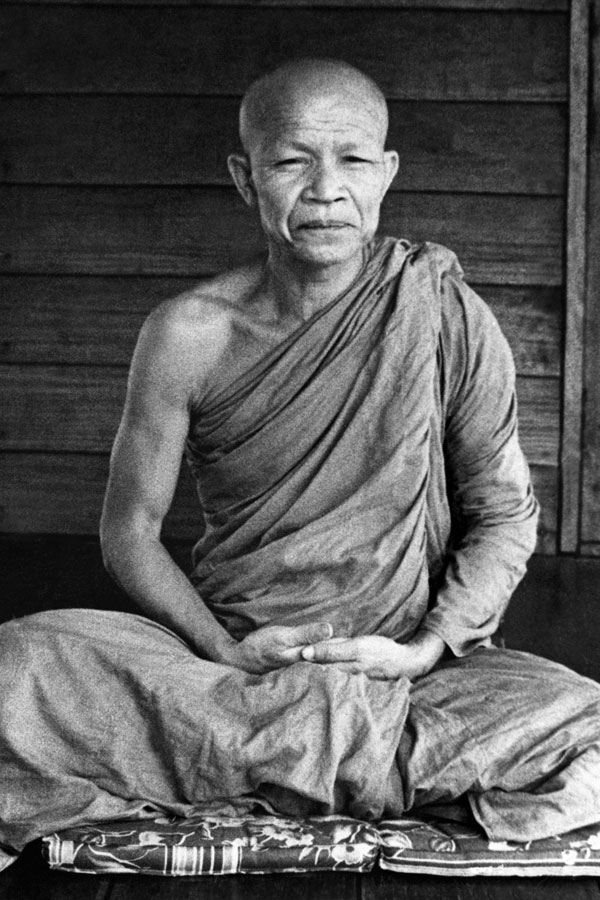

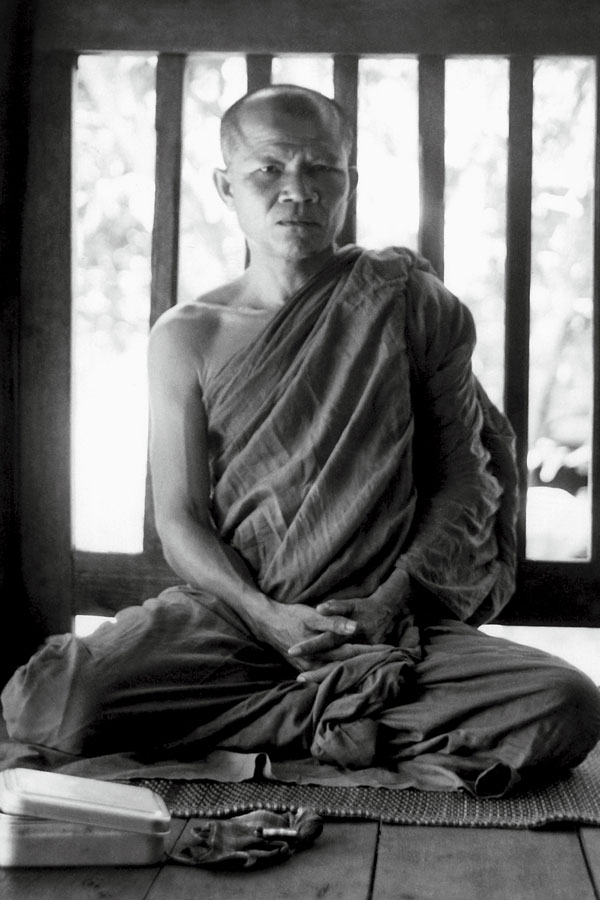

Phra Ajaan Maha Bua Nānampanno

(1913 – 2011)

AJAAN MAHĀ BOOWA’S STORY IN HIS OWN WORDS:

My mother was a wonderfully patient and devoted woman. She told me that of all the sixteen children she carried to birth, I was by far the most troublesome in the womb. I was either so still in her stomach that she thought I must have already died, or I was thrashing around so violently that she thought I must have been on the verge of death. The closer I came to birth, the worse those extremes became.

Just before I was born, my mother and my father each had an auspicious dream. My father dreamed that he had received a very sharp knife, pointed at the tip with an elephant tusk handle and encased in a silver sheath. My father felt very pleased.

My mother, on the other hand, dreamed that she had received a pair of gold earrings which were so lovely that she couldn’t resist the temptation to put them on and admire herself in the mirror. The more she looked, the more they impressed her.

My grandfather interpreted these two dreams to mean that the course of my life would follow one of two extremes. If I chose the way of evil, I would be the most feared criminal of my time. My character would be so fearsome that I was bound to end up being a crime boss of unprecedented daring and ferocity who’d never allow himself to be captured alive and imprisoned, but would hide out in the jungle and fight the authorities to the death.

At the other extreme, if I chose the way of virtue, my goodness would be unequalled. I’d be bound to ordain as a Buddhist monk and become a field of merit for the world.

When I grew up I noticed that all the older boys were getting married, so I thought that’s what I wanted too. One day, an old fortune teller came to visit the house of my friend. In the course of conversation, my friend blurted out that he wanted to ordain as a monk. The old man looked a bit annoyed and then asked to see the boy’s hand.

“Let’s take a look at the lines in your palm to see if you’re really going to be a monk. Oh! Look at this! There’s no way you’ll ordain.”

“But I really want to ordain!”

“No way! You’ll get married first.”

I suddenly got an itch to ask the old man about my fortune, since I was hoping to marry at that time. I had no intention to ordain. When I stuck my hand out, the old man grabbed it and exclaimed: “This is the guy that’s going to ordain!”

“But I want to get married.”

“No way! Your ordination line is full. Before long you’ll be a monk.”

My face went flush because I wasn’t intending to be a monk at all. I wanted to have a wife.

It was strange really. After that, whenever I thought of marrying a girl, some obstacle would arise to prevent it. I even had a narrow escape after I ordained, when a girl I previously had a crush on came looking for me at the monastery, only to find that I had just moved to another place. Had she caught me in time, who knows…

While I was growing up, I had no particular desire to become a monk. It took me awhile to focus my attention on it. When I was twenty I fell seriously ill, so ill that my parents were constantly sitting at my bedside. My physical symptoms were severe. At the same time, a decision on whether or not to ordain weighed heavily on my mind. I felt the Lord of Death closing in on me. My whole life seemed to be in the balance.

My parents sat anxiously beside me not daring to speak. My mother, who was usually very talkative, just sat there crying. Eventually my father couldn’t hold back his tears. They both thought I was going to die that night. Seeing my parents crying in despair, I made the solemn vow that should I recover from that illness, I would ordain as a Buddhist monk for their sake. As though in response to my intense resolve, my symptoms began to slowly fade away; by dawn they had disappeared completely. Instead of dying that night as expected, I made a full recovery.

But following my recovery, the intensity of my resolve waned. My inner virtue kept reminding me that I had made a solemn promise to ordain, so why was I procrastinating? Several months of indecision passed, even though I kept acknowledging my failure to live up to my resolution. Why hadn’t I ordained yet? I knew I had no choice but to ordain. I had to honor the agreement I made with the Lord of Death: my life in exchange for ordination. I willingly conceded that ordination was inevitable. I wasn’t trying to avoid it, but I needed a catalyst. That catalyst came during a frank discussion with my mother. Both she and my father were pleading with me to ordain. Finally their tears forced me to make the decision that marked my path in life.

My father wanted me to ordain so badly that he began to cry. As soon as my father started crying, I was startled. My father’s tears were no small matter. I reflected on my father’s tears for three days before finalizing my decision. At the end of the third day, I approached my mother and announced my intention to ordain, adding the provision that I be allowed the freedom to give up the robes whenever I felt inclined. I made it clear that I wouldn’t ordain if I was forbidden to disrobe. But my mother was too clever. She said that if I wanted to disrobe immediately after the ordination ceremony, in front of all the people in attendance, she wouldn’t object. She’d be satisfied to see me standing there in yellow robes. That was all she asked. Of course, who would be foolish enough to immediately disrobe right there in front of the preceptor with the whole village in attendance? My mother easily outsmarted me on that one.

Soon after my ordination, I began reading the story of the Buddha’s life, which immediately awakened a strong sense of faith in my heart. I was so moved by the Buddha’s struggle to attain Enlightenment that tears rolled down my cheeks as I read. Contemplating the scope of his attainment instilled in me a fervent desire to gain release from suffering. Toward that purpose, I decided to formally study the Buddha’s teachings as a preparation for putting them into practice. With that aim in mind, I made a solemn vow to complete the third grade of Pāli studies. As soon as I passed the third-level Pāli exams, I planned to follow the way of practice. I had no intention to study further or take exams for the higher levels.

When I traveled to Chiang Mai to take my exams, by chance Venerable Ajaan Mun arrived at Wat Chedi Luang in Chiang Mai at the time I did. As soon as I learned that he was staying there, I was overwhelmed with joy. When I returned from my alms round next morning, I learned from another monk that Ajaan Mun left for alms on a certain path and returned by the very same path. This made me even more eager to see him. Even if I couldn’t meet him face to face, I’d be content just to have a glimpse of him before he left.

The next morning, before Ajaan Mun went on his alms round, I hurried out early for alms and then returned to my quarters. From there, I kept watch on the path by which he would return, and before long I saw him coming. With a longing that came from having wanted to see him for such a long time, I peeked out from my hiding place to catch a glimpse of him. The moment I saw him, a feeling of complete faith arose within me. I felt that because I had now seen an Arahant, I hadn’t wasted my birth as a human being. Although no one had told me that he was an Arahant, my heart became firmly convinced of it the moment I saw him. At the same time, a feeling of sudden elation hard to describe came over me, making my hair stand on end.

When I had passed my Pāli exams, I returned to Bangkok with the intention of heading out to the countryside to practice meditation in line with my vow. But when I reached Bangkok, the senior monk who was my teacher insisted that I stay on. He was keenly interested to see me further my Pāli studies. I tried to find some way to slip away, because I felt that the conditions of my vow had been met the moment I had passed my Pāli exams. Under no circumstances would I study for or take the next level of Pāli exams.

It’s my temperament to value truthfulness. Once I’ve made a vow, I won’t break it. Even life I don’t value as much as a vow. So now I had to find some way to go out to practice. By a fortunate turn of events, that senior monk was suddenly invited out to the provinces, which gave me a chance to leave Bangkok while he was away. Had he been there, it would have been hard for me to get away, because I was indebted to him in many ways and probably would have felt such deference for him that I would have had difficulty leaving. But as soon as I saw my chance, I decided to make a vow that night, asking for an omen from the Dhamma to reinforce my determination to leave.

After finishing my chants, I made my vow: the gist of which was that if my going out to meditate in line with my earlier vow would go smoothly and fulfill my aspirations, I wanted an unusual vision to appear to me, either in my meditation or in a dream. But if I’d be denied the chance to practice, or if having gone out I’d meet with disappointment, I asked that the vision show the reason why I’d be disappointed. On the other hand, if my departure was to fulfill my aspirations, I asked that the vision be extraordinarily strange and amazing. With that, I sat down to meditate. When no visions appeared during the long period I sat meditating, I stopped to rest.

As soon as I fell asleep, however, I dreamed that I was floating effortlessly above a vast celestial metropolis. Stretching beneath me as far as the eye could see was an extremely impressive sight. All the houses looked like royal palaces, shining brightly as they glittered in the sunlight, as though made of solid gold. I floated three times around the metropolis and then returned to earth. As soon as I returned to earth, I woke up. It was four o’clock in the morning. I quickly got up with a feeling of fullness and contentment in my heart, because while I floated around the metropolis, my eyes were dazzled by many strange and amazing sights. I felt happy and very pleased with my vision. I thought that my hopes were sure to be fulfilled. I had never before seen such an amazing vision, and one that coincided so nicely with my vow. I really marveled at my vision that night. Early the next morning, I went to take leave of the senior monk in charge of the monastery, who willingly gave me permission to go.

From the very start of my practice, I was very earnest and committed – because that’s the sort of person I am. I don’t play around. When I take a stance, that’s how it has to be. When I set out to practice, I had only one book – the Pāṭimokkha – in my shoulder bag. Now, I’d strive for the full path and the full results. I planned to give it my all – to give it my life. I wasn’t going to hope for anything short of freedom from suffering. I felt sure that I would attain that release in this lifetime. All I asked was that someone show me that the paths, the fruitions and Nibbāna were still attainable. I would give my life to that person and to the Dhamma, without holding anything back. If it meant death, I’d die practicing meditation. I wouldn’t die in ignoble retreat. My heart was set like a stone post.

I spent the next rains in Cakkaraad district of Nakhon Ratchasima province, because I hadn’t been able to catch up with Ajaan Mun. As soon as I got there, I began accelerating my efforts, practicing both day and night; and it wasn’t long before my heart attained the stillness of samādhi. I wasn’t willing to do any other work aside from the work of sitting and walking meditation, so I pushed myself until my samādhi was really solid.

One day, just as my mind became calm and concentrated, a vision appeared in my meditation. I watched as a white-robed renunciant walked up and stood about 6 feet in front of me. He was an impressive looking man of about fifty who was impeccably dressed and had an unusually fair complexion. As I gazed at him, he looked down at his hands and started to count on his fingers. He counted one finger at a time until he reached nine, then glanced up at me and said, “In nine years you’ll attain.”

Later, I contemplated the meaning of this vision. The only attainment that I truly desired was freedom from suffering. By that time, I had been ordained for seven years, and it hardly seemed likely that two more years gave me enough time to succeed. Surely it couldn’t be that easy. I decided to begin counting from the year I left to begin practicing. By that reckoning, I should attain my goal in nine years’ time, in my sixteenth rains retreat. If the vision was indeed prophetic, then that timeframe seemed quite reasonable.

When I finally reached Venerable Ajaan Mun, he taught me the Dhamma as if it came straight from his heart. He would never use the words, “It might be like that” or “It seems to be like this” because his knowledge came directly from personal experience. It was as though he kept saying, “Right here. Right here.” Where were the paths, the fruitions and Nibbāna? “Right here. Right here.” My heart was convinced, really convinced. So I made a solemn vow: As long as he was still alive, I would not leave him as my teacher. No matter where I went, I’d have to return to him. With that determination, I accelerated my efforts in meditation.

Several nights later, I had another amazing vision. I dreamed that I was fully robed, carrying my bowl and umbrella-tent and following an overgrown trail through the jungle. Both sides of the trail were a mass of thorns and brambles. My only option was to continue following the trail, which was just barely a path, just enough to give a hint of where to go.

Shortly I reached a point where a thick clump of bamboo had fallen across the trail. I couldn’t see which way to continue. There was no way around it on either side. How was I going to get past it? I peered here and there until I finally saw an opening, a tiny opening right along the path, just enough for me to squeeze my way through together with my bowl.

Since there was no other option, I removed my outer robe and folded it up neatly. I removed the bowl strap from my shoulder and crawled through the opening, dragging my bowl by its strap and pulling my umbrella-tent behind me. I was able to force my way through, dragging my bowl, my umbrella-tent and my robe behind me; but it was extremely difficult. I kept at it for a long time until I finally worked my way free. Then, I pulled my bowl until my bowl came through. I pulled my umbrella-tent and my robe, and they came through. As soon as everything was safely through, I put on my robe again, slung my bowl over my shoulder and told myself, “Now I can continue.”

I followed that overgrown trail for another 100 feet. Then, looking up, I suddenly saw nothing but wide-open space. In front of me appeared a great ocean. Looking across it, I saw no further shore. All I could see was the shore where I stood and a tiny island sitting way out in the distance, like a black speck on the edge of the horizon. I was determined to head for that island. As soon as I walked down to the water’s edge, a boat came up to the shore and I got in. The boatman didn’t speak to me at all. As soon as I got my bowl and other things in the boat and sat down, the boat sped out to the island, without my having to say a word. I don’t know how it happened. It just sped out to the island. There didn’t seem to be any disturbances or waves whatsoever. Gliding silently, we arrived in a flash – because, after all, it was a dream.

As soon as we reached the island, I got my things out of the boat and went ashore. The boat disappeared immediately, without my saying even a word to the boatman. I slung my bowl over my shoulder and climbed up the island. I kept climbing until I saw Ajaan Mun sitting on a small bench, pounding betel nut as he watched me climb towards him. “Mahā,” he said, “how did you get here? Since when has anyone come that way? How were you able to make it here?”

“I came by boat.”

“Oho. That trail is really difficult. Nobody dares to risk his life coming that way. Very well then. Now that you’re here, pound my betel for me.” He handed me his betel pounder, and I pounded away – chock, chock, chock. After the second or third chock, I woke up. I felt somewhat disappointed. I wished I could have continued with the dream to at least see how it ended.

The next morning, I went to tell my vision to Ajaan Mun. He interpreted it very well. “This dream,” he said, “is very auspicious. It shows a definite pattern for your practice. Follow the practice in the way that you’ve dreamed. In the beginning, it will be extremely difficult. You have to give it your best effort. Don’t retreat. The beginning part where you made it through the clump of bamboo: that’s the difficult part. The mind will make progress only to slip back, over and over again. So give it your best. Don’t ever retreat. Once you get past that, it’s all wide open. You’ll get to the island of safety without any trouble. That’s not the hard part. The hard part is here at the beginning.”

Taking his words to heart, I focused on my meditation with renewed diligence. My samādhi had been erratic for over a year by that time, so my meditation practice was constantly up and down. Again and again, it advanced to full strength only to deteriorate as before. It wasn’t until April that I found a new approach, focusing on my meditation theme in a new way that made my concentration really solid. From that point on, I was able to sit in meditation all night long. My mind was able to settle down fully, which allowed me to continue accelerating my efforts. Speaking of the difficulties in the beginning stages of practice that my vision had predicted: that constant struggle to bring the mind under control was the most difficult part for me.

One day – during a time when I was extremely wary of Ajaan Mun – I lay down in the middle of the day and dozed off. As I slept, Ajaan Mun appeared in a dream to scold me: “Why are you sleeping like a pig? This is no pig farm! I won’t tolerate monks coming here to learn the art of being a pig. You’ll turn this place into a pigsty!” His voice bellowed, fierce and menacing, frightening me and causing me to wake with a start. Dazed and trembling, I stuck my head out the door expecting to see him. I was generally very frightened of him anyway; but I had forced myself to stay with him despite that. The reason was simple: it was the right thing to do. Besides, he had an effective antidote for pigs like me. In a panic, I looked around in all directions, but I didn’t see him anywhere. Only then did I begin to breathe a bit easier.

Later when I had a chance, I told Ajaan Mun what happened. He very cleverly explained my dream in a way that relieved my discomfort, “You’ve just recently come to live with a teacher, and you are really determined to do well. Your dream simply mirrored your state of mind. That scolding you heard, reproaching you for acting like a pig, was the Dhamma warning you not to bring pig-like tendencies into the monkhood and the religion.”

Following that, I took every opportunity to be more diligent. Since my arrival, I had heard Ajaan Mun talk a lot about the ascetic practices – such as the practice of accepting only the food received on one’s alms round. He himself was very strict in observing these practices. So I vowed to take on special ascetic practices during the rains retreat, which I diligently maintained. I vowed to eat only the food I got while on my alms round. If anyone tried to put food in my bowl aside from the food I had received on my round, I wouldn’t accept it and wouldn’t be interested in it. I was unwilling to compromise my principles, which is why I wouldn’t let anyone ruin my ascetic practice by putting food in my bowl – with the exception of Ajaan Mun, who I respected with all my heart. With him, I’d give in and let him put food in my bowl when he saw fit.

Coming back from my alms round, I’d quickly put my bowl in order, taking just the small amount of food I planned to eat – because during the rains I never ate my fill. I determined to take only about 60 to 70 percent of what would make me full. So I cut back my food consumption about 30 to 40 percent. It wasn’t convenient to go without food altogether, since I always had duties involved with the group. I myself was like one of the senior monks in the group, in a behind-the-scenes sort of way; though I never let on. I was involved in looking after peace and order within the monastic community. I didn’t have much seniority – just over ten rains – but Ajaan Mun was kind enough to trust me in helping him look after the monks and novices.

When I had put my bowl in order, I set it out of the way behind my seat, right against the wall next to a post. I put the lid on and covered it with a cloth to make doubly sure that no one would put any food in it. But when Ajaan Mun put food in my bowl, he had a clever way of doing it. After I gave him the food that I prepared for him and had returned to my place; after we had chanted our blessing and during the period of silence when we contemplated our food – that’s when he’d do it: right when we were about to eat.

At that time, I was absolutely determined to not let this observance be deficient. I wanted my practice to be complete, both in the letter of its strict observance and in the spirit of my determination to stick to it. But because of my love and respect for Ajaan Mun, I accepted his gifts even though I did not feel comfortable about it. But he probably saw that there was pride lurking in my vow to observe this practice, so he helped bend it a little to give me something to contemplate, thus dissuading me from being too rigid in my views. Therein lies the difference between a principle in the practice and a principle in the heart. I was right in my earnestness to follow a strict practice; but at the same time, I was wrong in terms of the levels of Dhamma that are higher and more subtle than that.

Comparing myself with Venerable Ajaan Mun, I could see that we were very different. When Ajaan Mun looked at something, he comprehended it thoroughly and in a way that was just right from every angle in the heart. He never focused on only one side, but always used wisdom to see the broader picture. This lesson I learned many times while living with him.

In that way, studying with Ajaan Mun wasn’t simply a matter of studying teachings about the Dhamma. I had to adapt myself to the practices he followed until they were firmly impressed in my own thoughts, words and deeds. Living with him for a long time allowed me to gradually observe his habits and his practices, and to understand the reasoning behind them, until that knowledge was firmly embedded in my heart. I felt a great sense of security while living with him, because he himself was all Dhamma. At the same time, staying in his presence forced me to always be watchful and restrained.

Ajaan Mun had a habit of chanting every night for several hours. Hearing him softly chanting in his hut one evening, I had the mischievous urge to sneak up and listen. I wanted to find out what he chanted at such length every night. But as soon as I crept up close enough to hear him clearly, his voice stopped and remained silent. This didn’t look good, so I quickly backed away and stood listening from a distance. No sooner had I backed away than I heard the low cadence of his chanting start up again, now too faint to be heard clearly. So again I sneaked forward – and again he went silent. In the end, I never did find out what he was chanting. I was afraid that if I stubbornly insisted on eavesdropping, a bolt of lightning might strike and a sharp rebuke thunder out.

Meeting him the next morning, I glanced away. I did not dare look him in the face. But he looked directly at me with a sharp, menacing glare. I learned my lesson the hard way: never again did I dare to sneak up and try to listen in on his chanting. I was afraid I would receive something severe for my trouble.

I had heard that Ajaan Mun could read other people’s minds, and this intrigued me. So one day I decided to test him to see if it was true. In the afternoon, I prostrated three times before the Buddha statue and set up a determination in my heart: should Ajaan Mun know what I am thinking at this moment, then let me receive a clear and unmistakable sign that will dispel all my doubts.

Later that afternoon, I went to Ajaan Mun’s hut to pay my respects. When I arrived, he was sewing patches on his robes, so I offered to help. As soon as I approached him, his expression changed and his eyes grew fierce. Something didn’t feel right. I tentatively put my hand out to take a piece of cloth, but he quickly snatched it from my grasp with a short grunt of displeasure. “Don’t be a nuisance!” Things didn’t look good at all, so I sat quietly and waited. After a few minutes of tense silence, Ajaan Mun spoke, “Normally a practicing monk has to pay attention to his own mind and observe his own thoughts. Unless he’s crazy, he doesn’t expect someone else to look into his mind for him.”

In the lengthy silence that followed, I felt humbled and my mind surrendered to him completely. I made a solemn vow never again to challenge Ajaan Mun. After that, I respectfully asked permission to help him sew his robe, and he made no objection.

When staying with Ajaan Mun, I felt as though the paths, the fruitions and Nibbāna were nearly within my grasp. Everything I did felt solid and brought good results. But when I left him to go wandering in the forest alone, all that changed. Because my mind still lacked a firm basis, doubts began to arise. When doubts arose that I couldn’t handle myself, I’d have to go running back to him for advice. Once he suggested a solution, the problem usually disappeared in an instant, as though he had cut it away for me. Sometimes, I would leave him for only five or six days when a problem started bothering me. If I couldn’t solve the problem the moment it arose, I’d head right back to him the next morning, because some of those problems were very critical. Once they arose, I needed advice in a hurry.

Speaking of effort in the practice, my tenth rains – beginning from the April after my ninth rains – was when I made the most intense effort. In all my life, I have never made a more vigorous effort than I did during my tenth rains. The mind went all out, and so did the body. From that point on, I continued making progress until the mind became solid as a rock. In other words, I was so skilled in my samādhi that the mind was as unshakeable as a slab of rock. Soon I became addicted to the total peace and tranquility of that samādhi state; so much so that my meditation practice remained stuck at that level of samādhi for five full years.

Once I was able to get past my addiction to samādhi, thanks to the hard-hitting Dhamma of Ajaan Mun, I set out to investigate. When I began investigating with wisdom, progress came quickly and easily because my samādhi was fully prepared. The path forward was wide-open and spacious, just as my vision had prophesied.

By the time I reached my sixteenth rains retreat, my meditation was progressing to the point where mindfulness and wisdom were circling around all external sensations and all internal thought processes, meticulously investigating everything without leaving any aspect unexplored. At that level of practice, mindfulness and wisdom acted in unison like a Wheel of Dhamma, revolving in continuous motion within the mind. I began to sense that the attainment of my goal was close at hand. I remembered my earlier vision predicting attainment in that year and accelerated my efforts.

But by the end of the retreat, I still had not attained. My visions had always prophesied accurately before, but I began to suspect that this one had lied to me. Being somewhat frustrated, I decided to ask a fellow monk who I trusted what he made of the discrepancy. He immediately retorted that I must calculate a full year: from the beginning of the sixteenth rains retreat to the beginning of the seventeenth. Doing that gave me nine more months of my sixteenth year. I was elated by his explanation and got back to work in earnest.

Having been gravely ill for many months, Ajaan Mun passed away shortly after my sixteenth rains retreat. Ajaan Mun was always close at hand and ready to help resolve my doubts and provide me with inspiration. When I approached him with meditation problems that I was unable to solve on my own, those issues invariably dissolved away the moment he offered a solution. The loss of Ajaan Mun as a guide and mentor profoundly affected my hopes for attainment. Gone were the easy solutions I had found while living with him. I could think of no other person capable of helping me solve my problems in meditation. I was now completely on my own.

Fortunately, the current of Dhamma that flowed through my meditation had reached an irreversible stage. By May of the next year, my meditation had arrived at a critical phase. When the decisive moment arrived, affairs of time and place ceased to be relevant. All that appeared in the mind was a splendid, natural radiance. I had reached a point where nothing else was left for me to investigate. I had already let go of everything – only that radiance remained. Except for the central point of the mind’s radiance, the whole universe had been conclusively let go.

At that time, I was examining the mind’s central point of focus. All other matters had been examined and discarded; there remained only that one point of “knowingness.” It became obvious that both satisfaction and dissatisfaction issued from that source. Brightness and dullness – those differences arose from the same origin.

Then, in one spontaneous instant, Dhamma answered the question. The Dhamma arose suddenly and unexpectedly, as though it were a voice in the heart: “Whether it is dullness or brightness, satisfaction or dissatisfaction, all such dualities are not-self.” The meaning was clear: Let everything go. All of them are not-self.

Suddenly, the mind became absolutely still. Having concluded unequivocally that everything without exception is not-self, it had no room to maneuver. The mind came to rest – impassive and still. It had no interest in self or not-self, no interest in satisfaction or dissatisfaction, brightness or dullness. The mind resided at the center, neutral and placid. It appeared inattentive; but, in truth, it was fully aware. The mind was simply suspended in a still, quiescent condition.

Then, from that neutral, impassive state of mind, the nucleus of existence – the core of the knower – suddenly separated and fell away. Having finally been stripped of all self-identity, brightness and dullness and everything else were suddenly torn asunder and destroyed once and for all.

In the moment when the mind’s fundamental delusion flipped over and fell away, the sky appeared to come crashing down as the entire universe trembled and quaked. When all delusion separated and vanished from the mind, it seemed as if the entire world had fallen away and vanished along with it. Earth, sky – all collapsed in an instant.

On May 15th of that year, the 9-year prediction from my earlier vision was fully realized. I finally reached the island of safety in the middle of the great wide ocean.

Several years later, while I was staying at Baan Huay Sai, I experienced another amazing vision. Floating high up in the sky, I saw all the Buddhas from the past stretched out before me. As I prostrated before them, all the Buddhas were transformed into life-size solid gold statues. Pouring fragrant water, I performed a ritual bathing of all the golden Buddhas.

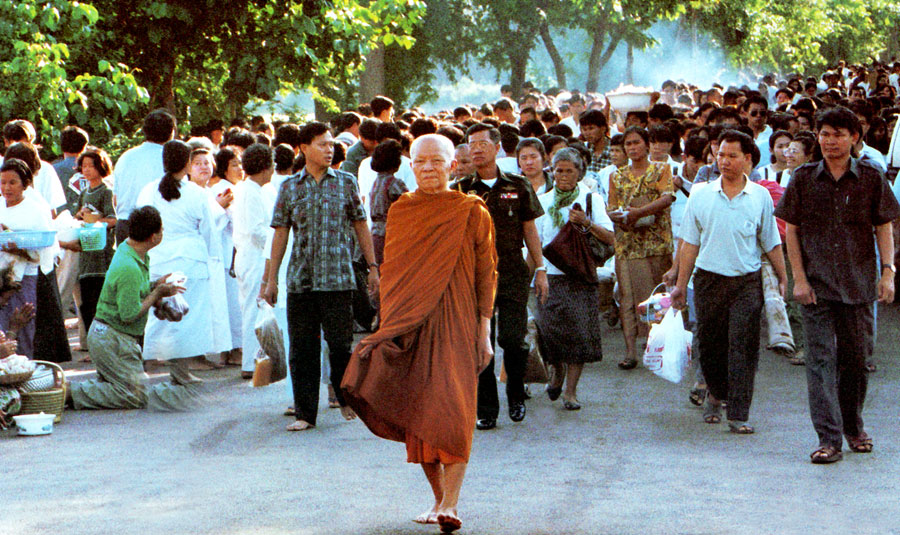

While floating back to the ground, I saw an enormous crowd of people stretching to the horizon in every direction. At that moment, precious holy water began streaming from my finger tips and from the palms of my hands, spraying out in all directions until it had showered the entire congregation.

As I floated above the ground, I looked down and saw my mother sitting in the crowd. Looking up, she implored of me, “Son, are you going to leave? Are you leaving?” I answered, “When I finish I’m going to leave, but you wait here.”

When I had finished spraying holy water in all directions, I floated down to the ground. My mother had spread a mat on the ground in front of her house, so I sat down and taught her the Dhamma.

Reflecting on this vision later, I realized that I would have to ordain my sixty-year-old mother as a white-robed nun. I wished to give her the best possible opportunity for spiritual development during her remaining years. So I quickly sent her a letter advising that she begin preparing for a nun’s ordination.

My place of birth was located in Udon Thani province, several hundred miles from Baan Huay Sai. Upon arriving at Baan Taad village, I found my mother eagerly anticipating her new life. Straightaway we set about preparing for her ordination. Recognizing that my mother was too old to wander with me through the forests, I looked for a suitable place in the vicinity of Baan Taad village to establish a forest monastery. When a maternal uncle and his friends offered a 70-acre piece of forested land about one mile south of the village, I gratefully accepted. I decided to settle there and build a monastery where both monks and nuns could live in peaceful seclusion. I instructed my supporters to build a simple grass-roofed, bamboo meeting hall and small bamboo huts for the monks and nuns.

The vision I had of teaching my mother foreshadowed the establishment of Baan Taad Forest Monastery, which completely changed my life forever. Before that, I roamed as I pleased. At the end of each rains retreat, I’d just disappear into the forest, content like a bird that has only its wings and its tail to look after. After that, I lived at my monastery and looked after my mother until the day she died.

Eventually, monks began to gather around me in larger and larger numbers, and I taught them to be resolute in their practice and to maintain Ajaan Mun’s lineage of renunciation, strict discipline and intensive meditation. Although I have a reputation for being fierce and uncompromising, more and more practicing monks have gravitated to Baan Taad Forest Monastery over the years, transforming it into a thriving center of Buddhist practice.

The enormous crowd of people in my vision began to become a reality. Gradually, little by little, my teaching began to spread, until it extended far and wide. Now, people from across Thailand and around the world come to listen to Luangta Mahā Boowa expound the Dhamma. Some travel here to hear me talk in person; some listen to recordings of my talks that are broadcast throughout Thailand on the radio and the Internet.

As I grew older, my exposure in Thai public life continued to expand with each passing year. When the economic crisis hit in 1997, I stepped in to help lift the nation from the depths of darkness: that is, from greediness on one level of society and from poverty on the other. I wanted Thais to focus on the causes of the crisis so that, by knowing the causes, they could change their behavior to prevent such an event from recurring. So I used the Help the Nation campaign not only to raise gold for the national treasury, but more importantly as a means to spread the Buddha’s teaching to a broader section of Thai society in an age when many Thai people are losing touch with Buddhist principles.

I have tried my utmost to help society. Within my heart, I have no sense of courage and no sense of fear; no such things as gain or loss, victory or defeat. My attempts to assist people stem entirely from loving compassion. I sacrificed everything to attain the Supreme Dhamma that I now teach. I nearly lost my life in search of Dhamma, crossing the threshold of death before I could proclaim to the world the Dhamma that I realized. Sometimes I talk boldly, as if I were a conquering hero. But the Supreme Dhamma in my heart is neither bold nor fearful. It has neither gain nor loss, neither victory nor defeat. Consequently, my teaching emanates from the purest form of compassion.

I can assure you that the Dhamma I teach does not deviate from those principles of truth that I myself have realized. The Lord Buddha taught the same message that I am conveying to you. Although I am in no way comparable to the Buddha, the confirmation of that realization is right here in my heart. All that I have fully realized within myself concurs with everything that the Lord Buddha taught. Nothing that I have realized contradicts the Lord Buddha in any way. The teaching that I present is based on principles of truth which I have long since wholeheartedly accepted. That’s why I teach people with such vigor as I spread my message throughout the world.

Cited from:

Ajaan Maha Boowa